Lessons from the Office of Warfighting Advantage

In college, I viewed the world through the lens of economics. I learned that life is essentially a study of how individuals and organizations allocate scarce resources to satisfy unlimited needs. It taught me to think in systems, analyze incentives, and model decision-making under constraints.

But models are tidy, and reality is messy.

My transition from abstract theory to operational reality happened when I joined the Navy’s Office of Warfighting Advantage (OWA). Suddenly, the “scarce resources” were not just capital or labor. They were national security, readiness, and human lives. This role did not just apply my economics background; it completely overhauled how I view leadership and problem-solving.

The Office of Warfighting Advantage

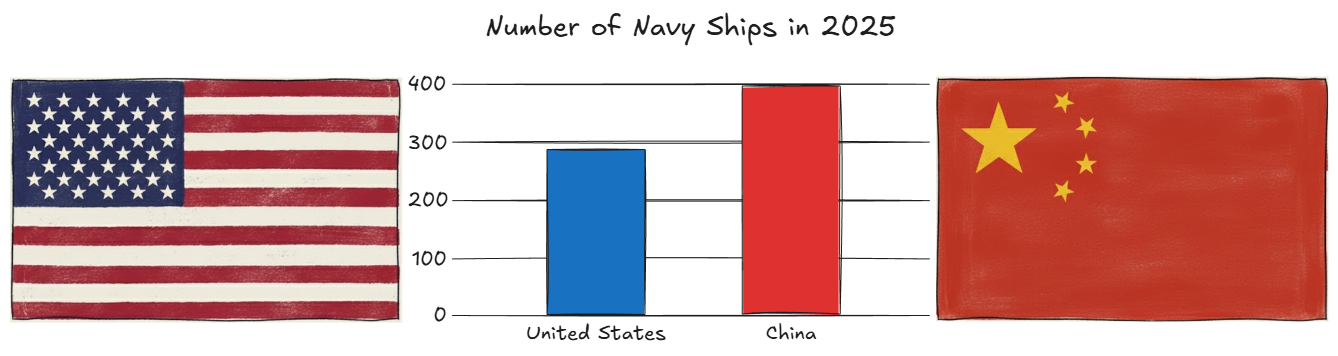

The Office of Warfighting Advantage exists to solve a terrifying math problem.

For decades, the United States Navy relied on overwhelming numerical superiority. We could simply out-build and out-gun any competitor. That era is over. Today, China possesses the largest navy in the world and a shipbuilding capacity that dwarfs American production. We can no longer guarantee victory through quantity alone; maintaining the status quo is a losing proposition.

OWA was established to secure a different kind of edge. If we cannot out-build the adversary, we must out-learn and out-think them. The office’s mission is to drive cultural change that prioritizes the quality of our people, the speed of our learning, and the honesty of our assessments.

The Framework: Get Real, Get Better

To modernize a 200-year-old institution, OWA deployed a framework called “Get Real, Get Better” (GRGB). It is built around a simple premise: Self-Assessment plus Self-Correction equals Continuous Improvement.

Organizations that honestly assess their performance and rapidly correct course will outpace those that cannot.

The Mindset

The framework begins with the mental attitudes that orient how we handle situations.

- Self-Assessment: This is enabled by Self-Awareness (seeing ourselves clearly) and Psychological Safety (a belief that it is safe to take risks and admit mistakes). We had to stop “broadcasting the green,” or reporting that everything was fine. Instead, we needed to “Embrace the Red.”

- Self-Correction: This is driven by a Growth Mindset (viewing failure as data rather than a character flaw) and Curiosity. When a setback occurs, the question shifts from “Who is to blame?” to “What can we learn?”

The Skillset

Mindset implies action. The GRGB skillset translates these attitudes into learnable behaviors:

- Acting Transparently: We align teams on clear standards and goals to ensure reality is visible to everyone.

- Focusing on What Matters Most: We stop trying to boil the ocean. Leaders must use proven methods to identify the biggest levers for improvement. They must relentlessly fix or elevate barriers by solving what they can locally and clearly communicating obstacles up the chain of command.

- Building Learning Teams: Excellence requires a culture of trust, respect, and specified ownership. Every team member must know exactly what they own and feel safe enough to innovate.

The Toolset

Finally, the framework provides structure to abstract concepts.

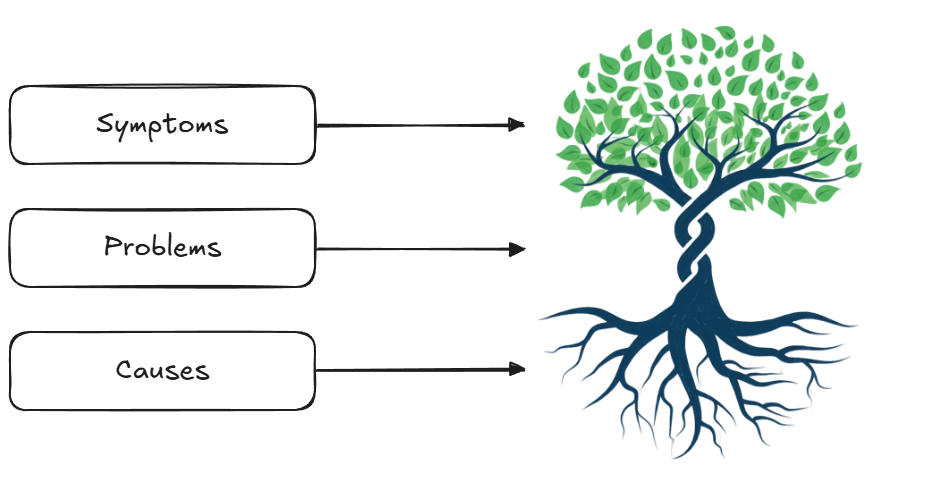

- Driver Trees map cause-and-effect relationships. They make complex, overwhelming problems visible and tractable.

- Process Maps visualize workflows to uncover hidden inefficiencies or bottlenecks.

- Root Cause Analysis identifies the source of failure. Instead of applying band-aid fixes to symptoms, it exposes the fundamental conditions that allowed the issue to occur.

What I Learned

Helping implement this framework across different commands taught me three lessons that apply to any organization, military or civilian.

1. Systems problems require systems thinking

The Navy’s operational setbacks, such as ship collisions or major fires, were rarely caused by individual incompetence. They were symptoms of systemic breakdowns. These included cultures where speaking up felt risky, or processes that prioritized the appearance of success over the reality of readiness.

You cannot fix a systems problem with an individual solution. You cannot rely on individual competence to overcome systemic dysfunction. You must look at the incentives, the culture, and the processes that govern behavior.

2. Principles transfer across contexts

I saw these principles applied in Naval Special Warfare, Navy Recruiting Command, and Naval Information Forces. These are radically different environments with different missions, yet these principles worked everywhere.

Why? Because the core requirements for human problem-solving are universal. Every organization struggles with clarity. Every team needs psychological safety. Whether you are running a destroyer or a startup, the formula remains the same: see yourself clearly, speak the truth about deficits, and build a system that learns faster than the competition.

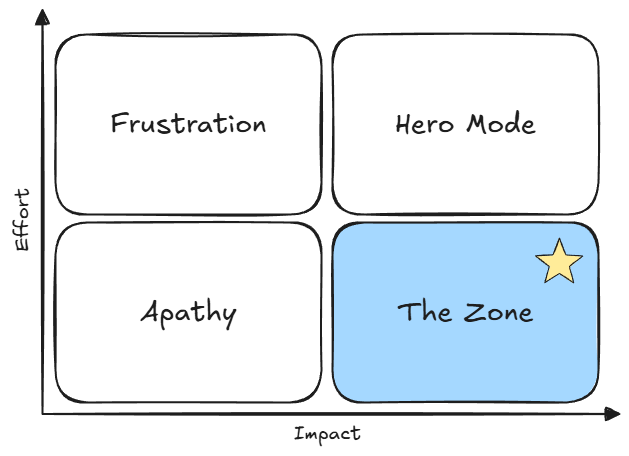

3. Sustainable excellence beats heroic effort

The Navy prides itself on a “Can-Do” attitude. However, there is a dark side to this. It can lead to relying on “Hero Mode,” or continuous maximum effort, to meet standard requirements.

If your team has to sprint, pull all-nighters, and bypass processes just to achieve a normal baseline, your system is broken. Sustainable excellence means operating in “The Zone.” This is a state of smooth, effortless professionalism that achieves high performance through reliable processes, not by burning out your people. If you are always surging just to survive the day-to-day, you have no capacity left for the actual crisis.

Looking Forward

After a decade supporting the Navy, these lessons are coming with me. The same questions that drove GRGB are just as relevant in technology as they are in national defense: How do you build systems that learn faster than they fail? How do you create environments where people surface problems instead of hiding them?

I’m now transitioning into DevOps engineering, where I’ll apply these frameworks to a different kind of infrastructure. This blog is where I’ll document that journey. Next up: why I chose this path, and how a decade of military problem-solving translates to building reliable systems.